Slide 2: A variety of approaches

exist for the treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD). Four

major approaches include psychodynamic, cognitive-behavioral,

humanistic, and family systems. Each approach perceives obsessive

compulsive disorder as an intrusive condition characterized by unwanted

repetitive and anxiety-producing thoughts accompanied by the compulsive

act of rituals the individual believes will protect them from the

anxiety (Hansell & Damour, 2008). The obsessions are thoughts or

impulses over which the individual has no control except to apply the

ritual for relief, and the compulsions make the individual feel driven

to do something - usually the ritualistic practice for the purpose of

relieving the anxiety (Hansell & Damour, 2008).

OCD

has a well-established biological component similar to other anxiety

disorders. According to the National Institutes of Health (2010)

anxiety produces affective physical reactions in people, and the

biological perspective views the activation or stimulation of the

nervous system and its excesses or deficiencies. There may also be

associated genetic predispositions, neuro-chemical, and hormonal

malfunctions (Schimelpfening, 2009). Emotion components include

underlying concerns or experiences that have not been openly addressed.

From a psychodynamic perspective, there may be pain and sadness

resulting from early childhood parental relations. Most psychologists

consider underlying conditions as a prelude to OCD (Hansell &

Damour, 2008).

The

cognitive-behavioral components of OCD include cognitive distortions of

oneself and one's environment. Anxiety is often the result of

maladaptive thought processes and dysfunctional thought patterns.

Misinterpreted situations, and the underestimation of emotional ability

may contribute to the disorder. As mentioned previously, behavioral

components include the obsessive thoughts or impulses which precedes the

application of ritualistic practice (Hansell & Damour, 2008). Each

approach has distinct perceptions of OCD and equally distinct methods

of management.

Freud

also theorized the symptoms of OCD were caused by misunderstood

punishment and rigid toilet training that led to internalized conflicts.

Other psychodynamic theorists considered OCD the result of the

cultural demand for cleanliness and neatness, as well as parental style

and punishment tactics during childhood. According to Fraum (2011),

"the fundamental issues that drive these symptoms include fear of

rejection or abandonment, as well as interpersonal issues regarding

intimacy, sex, control, power or other problems in their relationship"

(para. 11). Freud published a case study on a patient he called

Rat-man. He claimed he successfully treated the man for obsessive

thoughts and compulsive behaviors which Freud thought began from sexual

and punitive issues in his childhood (Wertz, 2003).

The

goal of the psychodynamic interventions is to help clients understand

the roots of their symptoms, gain greater self-acceptance, develop

better solutions to emotional conflicts, and decrease needs for

problematic defense mechanisms (Hansell & Damour, 2008). In the

case of OCD by relieving individuals’ stress, they will cease to need to

use the defense mechanism.

According to Abend (1996), psychodynamic

therapy focuses on pathological anxiety that arises from unconscious

emotional conflicts, so therapists in this discipline tend to use basic

psychodynamic techniques to address most anxiety disorders (Abend,

1996). Through an established bond between the patient and the

therapist, the patient is encouraged to speak freely to uncover the

roots of the anxiety, and to recall dreams. Guided imagery and movement

is also used in the psychodynamic approach. The therapist helps the

client identify and understand problems as a reaction to present and

past issues.

Since

the psychodynamic approach seeks to uncover unconscious directives, the

therapist must be capable of interpreting the patient's thoughts,

feelings, and dreams and assisting the patient to identify the

unconscious motives to help the patient resolve the conflicting

emotions. A significant part of psychodynamic therapy is the ongoing

bond built between the patient and the therapist and the trust within

the relationship will allow the patient to thoroughly investigate the

issues.

Uncovering

the roots of anxiety is effective in any anxiety disorder and

psychodynamic therapy has been successfully used in the development of

treatment goals, as well as, especially in group treatment (Wells,

Glickauf-Hughes, & Buzzell, 1990). The patients modify their

character by “evolving autonomous functions and partly through evolving

relationships with other individuals” (Wells, Glickauf-Hughes, &

Buzzell, 1990, p. 375). According to Bram and Björgvinsson ( 2004), in

severe cases of OCD cognitive behavioral therapy was more successful

than psychodynamic therapy alone and relieved more symptoms of the OCD.

Bram and Björgvinsson ( 2004) claim that training psychodynamic

clinicians to accommodate cognitive-behavioral techniques will help

successfully treat patients with OCD.

In

a cognitive behavioral intervention, the goal would be to change the

way the individual responds to the stimulus in effect, changing the

ritualistic response to the disturbing thoughts. For example, a client

may be asked to allow themselves to think about the disturbing thoughts

without engaging in the usual ritualistic behavior. According to

Hansell and Damour (2009), the goal of cognitive-behavioral therapy

would be to interrupt the ritualistic behavior to allow the client to

experience the dissipation of the anxiety even without the application

of the ritual. When the process of obsessive thoughts followed by

ritualistic behavior is interrupted, the behavior ceases to negatively

reinforce the anxiety, so the pattern is broken.

Cognitive

therapists teach strategies and perspectives for responding to the

challenges that life has to offer so that individuals can gain a greater

sense of self-efficacy (i.e. developing faith in their abilities to

achieve specified goals). Equally as important as knowledge, training,

experience, and credentials on the part of the cognitive therapist are

warmth, understanding, and compassion (Phillipson, n.d., para. 3).

Cognitive interventions for anxiety

disorders are generally goal-oriented and highly structured; cognitive

therapists take an active, directive stance toward the client and his or

her problems (Beck, Emery, & Greenberg, 2005). The therapist will

help the client identify the automatic responses to the disturbing

thoughts, and the negativity associated with the thoughts. They might

discuss the logic (or lack thereof) of the disturbing thoughts and

identify the distortions involved in such thinking. Ultimately, the

client will be taught how to challenge his or her typical thought

processes.

Because

the cognitive- behavioral perspective is based on the idea that people

learn from reinforcement from the environment, the strategies in

therapeutic application emphasize altering the pattern of reinforcement.

If a response causes disordered patterns, a change in response is

necessary (Phillipson, n.d.). The behaviorist approach claims all

learning takes place by the organisms adaptability to change according

to its environment, and changing that response alters the established

pattern.

Research

(Clark et al., 2003) finds cognitive-behavioral therapy effective in

treating anxiety disorders. According to Phillipson (n.d.), cognitive

behavioral treatment for obsessive-compulsive disorder provides the

client with effective tools with which to continually manage anxiety and

challenge internalized thinking. Rather than depending on a therapist

for longer periods, the client can immediately learn to use the

cognitive-behavioral tools. The behavioral tools are ultimately

important in the client's ability to continue the management of the

disturbing thoughts, and finally decrease the endless ritualizing.

Nathan and Gorman (2002) found the interventions were as effective used

alone as in combination with other behavioral techniques such as

relaxation training.

The

goal of humanistic therapy for OCD is to create an appropriate

environment by which the patient will be able to develop, mature, and

evolve, and as a result continue the process in healthy development

(Dombeck, 2006). I the humanistic view, psychological dysfunction is

caused by an interruption in development because of social and emotional

immaturity. By enabling natural development, the patient regains his

or her natural ability to proceed in a healthier direction. By

maintaining natural development, individuals continue along their

personal life pathway, and meeting their psychological needs.

One

well-known Gestalt technique is known as the empty chair technique

which is a visualization technique wherein the patient is directed to

imagine a person in the empty chair that sits in the therapists office.

By entering into a discussion with the imagined person, conflicts are

more easily resolved. The goal is to allow the patient to work with the

fears and emotions surrounding the issue, ultimately rendering the

situation less scary whereby the patient no longer needs to avoid the

other person or situation (Dombeck, 2006).

According

to Whelton (2004), depth of experience in psychotherapy is positively

related to outcome. In humanistic therapy, this depth is a normal

expectation and one goal of its application. This indicates feelings

and emotions are being processed and new more appropriate meanings are

formed as well as finding solutions to problems that create fear and

avoidance, and other issues that derail the natural human proclivity to

evolve. There is, however, no empirical research clarifying the

effective role of humanistic therapy in relieving the intrusive symptoms

of obsessive -compulsive disorder.

Family

systems approaches differ from psychodynamic, behavioral, and

humanistic approaches as they use the integration of the family in

recognizing and treating disordered emotions and behavior. Rather than

working with the individual having the specific problem, the whole

family is involved in the therapy. Psychological insight provided a new

platform for therapy that supported the family as an interrelated

system, not a group composed of members with random, unrelated

experiences. Rather than viewing the identified individual as affected

by motivations exclusive of the family, this new systems saw the

identified individual as a product of the family unit and "dysfunction

resided in the family as an interrelated system" (Plante, 2011, p. 60).

The

goal of family systems therapy is to treat the whole family and reduce

the dysfunction affecting all the members, but more severely expressed

by the identified family member. The issues of the identified

individual are acknowledged and addressed, although within the scope of

the family. As well as developing the identified individual, the system

also develops each family member as autonomous and independent while

re-establishing family solidarity (Plante, 2011). The system seeks a

balance between the function of the group and the independent individual

performance.

In family systems the therapist

guides the family in assessing their needs and defining goals.

Improving communication within the group is accomplished by several

techniques including reframing or changing perceptions within the group,

and paradoxical intention, which defines symptoms, especially those of

OCD to alleviate resistance to the therapy. Joining or developing a

rapport with the family allows the therapist to become more familiar

with the mechanisms by which the OCD became symptomatic. Through

establishing rapport with the family unit, the therapist can identify

any anxiety producing relationships or psychological enmeshment between

members (Plante, 2011). Furthermore, the therapist assists in the

recognition of disengagement of one or more members whereby the

individuals remove themselves from the family unit as a coping

mechanism, in this case the symptoms of disturbed thoughts and

ritualistic coping behavior. Alleviating the symptoms of OCD in one

family member includes understanding the anxiety and psychological

pressure the individual experiences. Identifying such issues will help

to establishing new ways of relating within the family, disabling the

individual's need for obsessive-compulsive behaviors.

The

communication approach seeks to re-establish healthy communication

within the family thereby eliminating unreasonable expectations,

inappropriate rules, and inaccurate assumptions between the individuals,

which may be causing the OCD symptoms. The structural approach aims to

disengage dysfunctional family patterns and balance relationships,

while the Milan approach establishes the therapist as an integral member

of the family, providing a neutral position and garnering respect for

the unit. The guidelines of all the specific techniques and strategies

embrace the general assumption that the family unit contains the

dysfunction causing the OCD, and issues are not exclusive to the

identified individual (Plante, 2011).

Unlike

the other three approaches addressed herein, family systems therapy

addresses inadequacies in the family unit. Although addressing these

relational issues, there is little evidence that family systems therapy

is efficient as an exclusive therapy for treating OCD. Carr (2000)

believes family therapy is an effective treatment "either alone or as

part of a multimodal or multisystemic treatment program for child abuse

and neglect, conduct problems, emotional problems, and psychosomatic

problems" (p. 48) although severe symptoms of OCD requires adjunct

therapy.

The major theoretical approaches

are philosophies about human behavior that provide psychologists with a

thematic conceptual understanding of mental health, illness, and

disorder. The approaches also provide a consistent parameter by which

to assess and treat the patient and a dependable plan of action in a

variety of situations and patient needs. Whereas the psychodynamic

perspective emphasizes the unconscious directives that influence the

individual's ability to maintain normal functioning, the foundation of

the cognitive-behavioral approach focuses on contemporary, measurable

and observable behavior. It uses classical and operant conditioning as

explanations for many types of behavior.

The

humanistic approach emphasizes the natural human ability to evolve and

develop and perceives people as "active, thinking, creative, and growth

oriented" (Plante, 2011, p. 133) and crave self-actualization. The

family systems approach views the unhealth of the individual as a

consequence of dysfunction in the family, and only by creating health

and solidarity within the family can the individual be freed from

symptoms of mental illness.

Psychologist

have become more integrating with their perspective preference and less

rigid to one particular theoretical approach. Each approach has

advantages for specific challenges, and some perspectives lend

themselves to particular research whereas others do not. The

integration of various theoretical perspectives in clinical psychology

allows the therapist to afford the broadest potential for successful

change within the individual. "Furthermore, as more research and

clinical experience help to uncover the mysteries of human behavior,

approaches need to be adapted and shaped in order to best accommodate

these new discoveries and knowledge" (Plante, 2011, p. 132). The human

psyche is a rich and complex maze of diverse needs and challenges,

served most appropriately by an equally elaborate and divergent palette

of treatments and interventions.

Abend, S. M. (1996). Psychoanalytic psychotherapy. In C. Lindemann

(Ed.), Handbook of the treatment of anxiety disorders (pp. 401–410). Northvale, NJ: Jason Aronson, Inc.

Allacentric. (n.d.). [Sisyphus]. Retrieved August 13, 2011, from http://www.seekersdigest.org/?p=920

Beck,

A. T., Emery, G., & Greenberg, R. L. (2005). Anxiety disorders

and phobias: A cognitive perspective. Cambridge, MA: Basic Books.

Bram,

A., & Björgvinsson, T. (2004). A psychodynamic clinician's foray

into cognitive-behavioral therapy utilizing exposure-response prevention

for obsessive-compulsive disorder. American Journal of Psychotherapy,

58(3), 304-320.

Carr,

A. (2000). Evidence-based practice in family therapy and systemic

consultation Child-focused problems. Journal of Family Therapy, 22(1),

29-60. doi: 10.1111/1467-6427.00137

Clark,

D. M., Ehlers, A., McManus, F., Hackmann, A., Fennell, M., Campbell,

H., ... Louis, B. (2003). Cognitive therapy versus fluoxetine in

generalized social phobia: a randomized placebo-controlled trial.

Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 71(6), 1058-1067. doi:

10.1037/0022-006X.71.6.1058

Dombeck,

M. (2006). Humanistic Psychotherapy. Mental Health, Depression,

Anxiety, Wellness, Family & Relationship Issues, Sexual Disorders

& ADHD Medications. Retrieved August 12, 2011, from

http://www.mentalhelp.net/poc/view_doc.php?type=doc

Freud

Museum Vienna. (2006). [Freud]. Retrieved August 14, 2011, from

http://www.glogster.com/glog.php?glog_id=14323765&scale=54&isprofile=true

Fraum, R. M. (2002). Obsessive Compulsive Disorder. Psychotherapy and Counseling for Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (OCD). Retrieved August 15, 2011, from http://www.psychologistcounselorpsychotherapist.com/obsessive-compulsive-disorder-ocd-nyc-westchester.aspx

Fraum, R. M. (2002). Obsessive Compulsive Disorder. Psychotherapy and Counseling for Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (OCD). Retrieved August 15, 2011, from http://www.psychologistcounselorpsychotherapist.com/obsessive-compulsive-disorder-ocd-nyc-westchester.aspx

Glogster.

(n.d.). [OCD Graphic]. Retrieved August 14, 2011, from

http://www.glogster.com/glog.php?glog_id=14323765&scale=54&isprofile=true

Hands

On Network. (2011). [Family]. Retrieved August 13, 2011, from

http://handsonblog.org/2010/07/06/6-ways-family-volunteering-benefits-businesses

Hansell, J., & Damour, L. (2008). Abnormal psychology. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Nathan, P. E., & Gorman, J. M. (2002). A guide to treatments that work (2nd ed.). New York: Oxford University Press.

National

Institutes of Health. (2010). Anxiety Disorders: MedlinePlus. National

Library of Medicine - National Institutes of Health. Retrieved August

13, 2011, from http://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/phobias.html

Per

Caritatem. (2011). [Human Graphic]. Retrieved August 15, 2011, from

http://percaritatem.com/2011/02/19/part-i-fanon-and-foucault-on-humanism-and-rejecting-the-%E2%80%9Cblackmail%E2%80%9D-of-the-enlightenment/

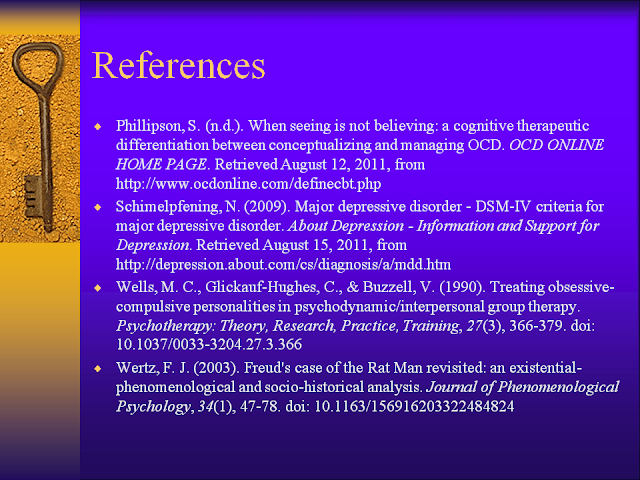

¨Phillipson,

S. (n.d.). When seeing is not believing: a cognitive therapeutic

differentiation between conceptualizing and managing OCD. OCD ONLINE

HOME PAGE. Retrieved August 12, 2011, from

http://www.ocdonline.com/definecbt.php

Schimelpfening,

N. (2009). Major depressive disorder - DSM-IV criteria for major

depressive disorder. About Depression - Information and Support for

Depression. Retrieved August 15, 2011, from

http://depression.about.com/cs/diagnosis/a/mdd.htm

Wells,

M. C., Glickauf-Hughes, C., & Buzzell, V. (1990). Treating

obsessive-compulsive personalities in psychodynamic/interpersonal group

therapy. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training, 27(3),

366-379. doi: 10.1037/0033-3204.27.3.366

Whelton, W. J. (2004). Emotional processes in psychotherapy: evidence across therapeutic modalities. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 11(1), 58-71. doi: 10.1002/cpp.392